The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a legal obligation to protect the public and ensure that the benefits of medicines outweigh the harms before being marketed to people.

But the agency’s increasing reliance on pharmaceutical industry money has seen the FDA’s evidentiary standards for drug approvals significantly decline.

The Need for Speed

Since the enactment of the 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), the FDA’s operations are kept afloat largely by industry fees which have increased over 30-fold from around $29 million in 1993 to $884 million in 2016.

Industry fees were meant to speed up drug approvals—and they did. In 1988, only 4 percent of new drugs introduced onto the global market were approved first by the FDA, but that rose to 66 percent by 1998 after its funding structure changed.

Now, there are four pathways within the FDA which are designed to speed up drug approvals: Fast Track, Priority Review, Accelerated Approval, and Breakthrough Therapy designation.

As a result, the majority (68 percent) of all new drugs are approved by the FDA via these expedited pathways.

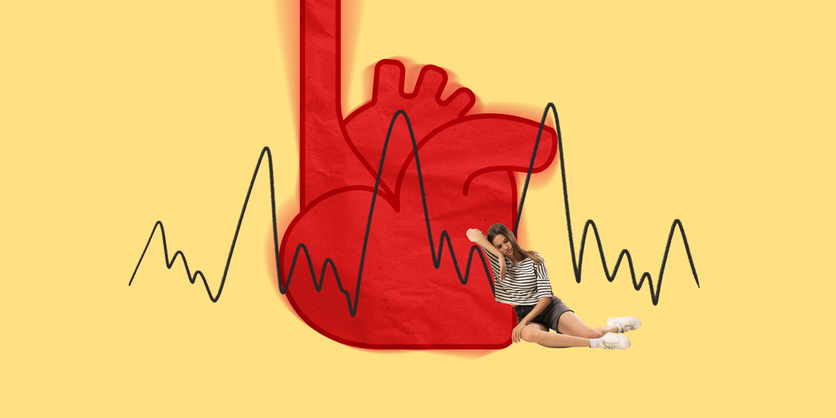

While it has improved the availability of transformative drugs to patients who benefit from early access, the lower evidentiary standards for faster approvals have undoubtedly led to harm.

A study focusing on drug safety found that following the introduction of PDUFA fees (1993-2004) there was a dramatic increase in drug withdrawals due to safety concerns in the U.S., compared to the period before PDUFA funding (1971-1992).

The researchers blamed changes in the “regulatory culture” at the FDA which had adopted more “permissive interpretations” of safety signals. Put simply, the FDA’s standards for approving certain medicines became less stringent.

Consequently, faster approvals have resulted in new drugs that are more likely to be withdrawn for safety reasons, more likely to carry a subsequent black-box warning, and more likely to have one or more dosages voluntarily discontinued by the manufacturer.

Evidence—Lowering the Bar

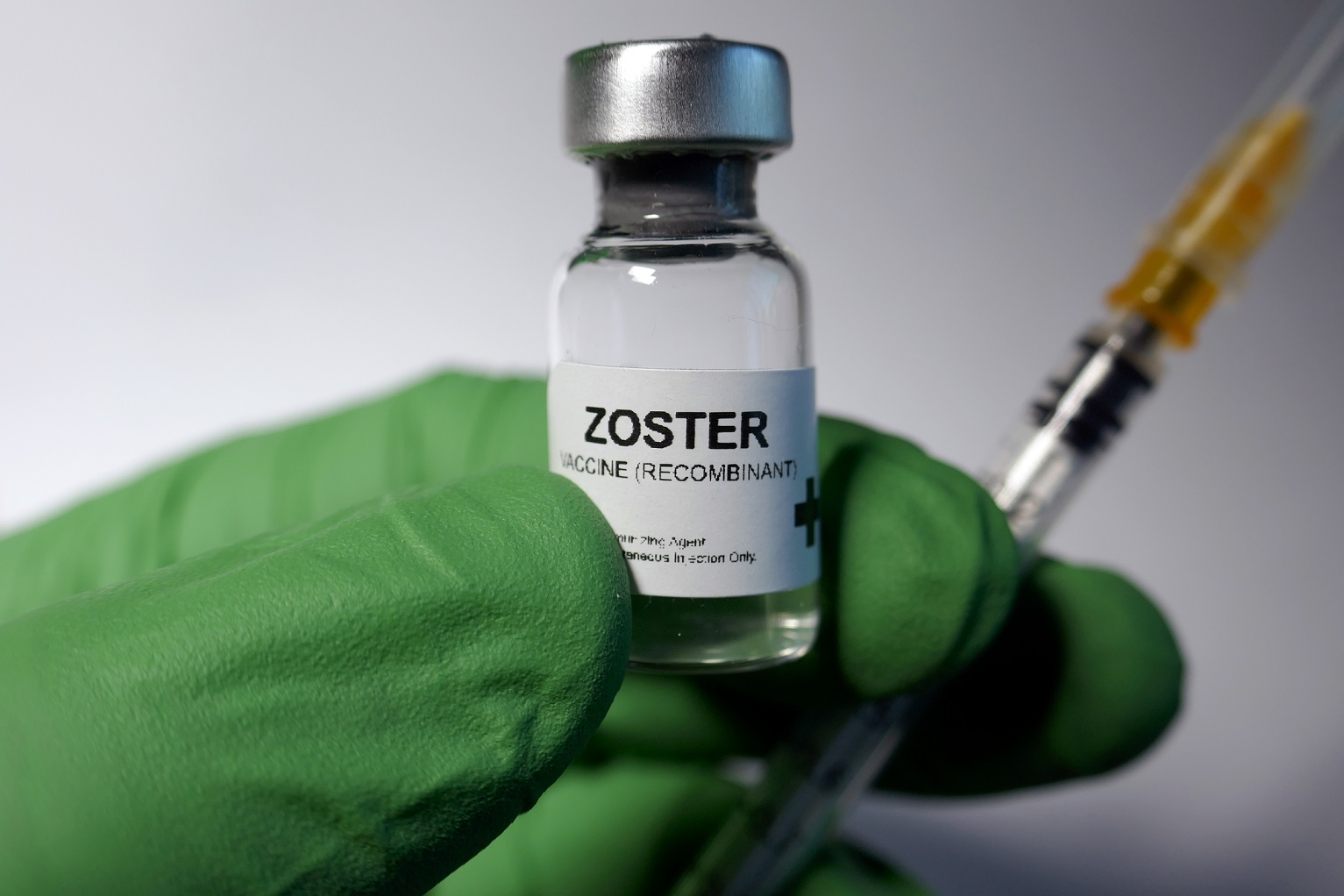

For accelerated drug approvals, the FDA accepts the use of surrogate outcomes (like a lab test) as a substitute for clinical outcomes.

For example, the FDA recently authorized the use of mRNA vaccines in infants based on neutralizing antibody levels (a surrogate outcome), rather than meaningful clinical benefits such as preventing serious COVID or hospitalization.

Also last year, the FDA approved an Alzheimer’s drug (aducanumab) based on lower β-amyloid protein levels (again, a surrogate outcome) rather than any clinical improvement for patients. One FDA advisory member who resigned over the controversy said it was the “worst drug approval decision in recent U.S. history.”

This lower standard of proof is becoming increasingly common. An analysis in JAMA found that 44 percent of drugs approved between 2005-2012 were supported by (inferior) surrogate outcomes, but that rose to 60 percent between 2015-2017.

It is a huge advantage to the drug industry because drug approvals may be based on fewer, smaller and less rigorous clinical trials.

—Pivotal trials

Traditionally, the FDA has required at least two ‘pivotal trials’ for drug approval, which are typically phase III clinical trials with ~30,000 subjects intended to confirm the drug’s safety and efficacy.

But a recent study found the number of drug approvals supported by two or more pivotal trials fell from 81 percent in 1995-1997 down to 53 percent by 2015-2017.

Other important design aspects of pivotal trials, such as “double blinding” fell from 80 percent in 1995-1997 down to 68 percent by 2015-2017 and “randomization” fell from 94 percent to 82 percent in that period.

Similarly, another study found that of the 49 novel therapeutics approved in 2020, more than half (57 percent) were on the basis of a single pivotal trial, 24 percent did not have a randomization component, and almost 40 percent were not double-blinded.

—Post-authorization studies

Following an accelerated approval, the FDA allows drugs onto the market before efficacy has been proven.

A condition of the accelerated approval is that manufacturers must agree to conduct “post authorization” studies (or phase IV confirmatory trials) to confirm the anticipated benefits of the drug. If it turns out that there is no benefit, the drug’s approval can be cancelled.

Unfortunately though, many confirmatory trials are never run, or they take years to complete and some fail to confirm the drug is beneficial.

In response, the FDA rarely imposes sanctions on companies for failing to adhere to the rules, drugs are rarely withdrawn and when penalties are applied, they are minimal.

An Embattled Agency

The FDA thinks its main problem is ‘public messaging’ so the agency is reportedly seeking a media-savvy public health expert to better articulate its messaging going forward. But the FDA’s problems run deeper than that.

A recent Government Accountability Office report revealed FDA staff (and other federal health agencies) did not report possible political interference in their work due to fear of retaliation and uncertainty about how to report such incidents.

Over the course of the pandemic, employees “felt that the potential political interference they observed resulted in the alteration or suppression of scientific findings… [and] may have resulted in the politically motivated alteration of public health guidance or delayed publication of covid-19-related scientific findings.”

Political interference has compounded an already problematic interference by the drug industry. The policy changes enacted since the 1992 PDUFA fees, have slowly corrupted the drug regulator, and many are concerned its decisions about drug approvals have prioritized corporate interests over public health.

Independent experts now say the declining evidentiary standards, shortening approval times, and increasing industry involvement in FDA decision-making, has led to distrust, not only of the agency, but in the safety and effectiveness of medicines, in general.

This article was reprinted with the author’s permission. It was originally published by the Brownstone Institute. Maryanne DeMasi is an investigative journalist and TV producer/presenter. She is a former medical scientist.

3 Responses

The FDA states clearly in its product approval process that it’s the product manufacturer that produces the safety studies, not the FDA. This alone opens up to fraud. The FDA approved GMOs, as an example, with a Monsanto study that was severely, criminally flawed, with a deliberate cut-off of less than three months, just before the harm and health damage began.

Soon on your late night television feed, immediately after the never ending slue of dangerous pharmaceutical ads and their frightening side effects; If you have ever consumed (insert the latest advertised drug here), you may be eligible for compensation. Call (insert law firm name here), for an immediate consultation to see if you qualify for a cash compensation reward. Such action reaction activity which followed the increasingly lax regulatory standards is already apparent and observable in many ways, television commercials being just one of them.

Obvious is obvious. We want DTC direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertisements OFF of the television, and we’re tired of the bait and switch with supposed but unproven ‘product safety’. Face it, the safety based regulatory mechanisms of the government are broken, from food, to products, to medicine, to environment. They’ve all been co opted by big corporate dollars. Otherwise the logical challenge is; If these drugs appear to be more harmful than cigarettes, why can’t cigarettes get television advertisement slots too? The last substances effectively regulated in America were lead, asbestos, and nicotine. Even then, it took them forever to get it right and still to this day the regulation is largely ineffective. The very last place we turn to for product safety advisement is the government, been that way for at least two decades by now.

Solutions are out there to manage these inevitable changes over time, but the will to adopt a check to balance is absent, due to perverse financial incentives and the nature of bureaucratic government itself. It is the old saying; we’re from the government are we are here to help. We had better broader safety expectations with tort where people and companies truly did lose everything if they harmed consumers, which that financial risk is no longer present because of government regulation. The act of government regulation abolishes the direct liability connection between product purveyor and product consumer, which is the root cause of the problem relating to corporate accountability for dangerous products brought to market. This is true from food to medicine to products. Fines based on income is one obvious solution if government regulation is to persist. As the table based fines represent minuscule proportions of the income gained by fast tracking dangerous drug approval. Liability lawyers only seek out the side line items in piecemeal bites, because there is inadequate financial incentive to go after the major offenders, otherwise legal teams get buried by corporate firms and plaintiffs always lose. Fines based on income would provide financial incentive for far more class action suits, successful ones too.

Other solutions may include a flat tax and scrapping the existing tax code, thereby removing the incentive to push more of these ads and products with anticipation of writing off costs, expenses, and the ever increasing probability of fines depending on how long the product continues to be available to market before the inevitable recall. A flat tax would remove the financial incentive on the corporate side to rush to market, as this would take a bite out of the corporate earnings structure and would bring actual financial harm to the company, if they were unable to write everything off. It would create more purveyor awareness of the safety of their own products. Couple that with fines based on income, we’d see a lot of systematic corrections which the open market would apply and no additional government growth would be necessary, except possibly more judges and courts to handle the tsunami of plaintiffs already harmed and soon to be harmed in the future by the most irresponsible predatory corporations pushing all these products.

This was an educational well written article. Thank you.

What standards? They have been falling by the wayside since the early 1990’s.