In a recent study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Watson et al. apply mathematical modeling to estimate that mass COVID-19 vaccinations saved between 14-20 million lives worldwide during the first year of the COVID-19 vaccination program. Previous Brownstone [Institute] articles by Horst and Raman have already pointed out several erroneous assumptions in the study regarding infection- vs. vaccine-derived immunity duration as well as the fact it did not account for vaccine adverse events and all-cause mortality risk.

Here, I summarize the mechanics of how the authors arrived at their estimates of deaths averted due to mass vaccinations. I then elaborate on how flawed assumptions in the model can lead to grossly inflated estimates of averted deaths, which may explain the study’s lack of face validity and internal consistency.

The study uses a generative model of COVID-19 transmission, infection, and mortality dynamics that includes 20-25 assumed parameters based on select literature (i.e. vaccine effectiveness against transmission, infection, and death, age-mixtures of each country, age-stratified infection fatality rates etc.) that is fitted to reported excess deaths in order to infer (but not validate) virus transmissibility across time in 185 countries.

The study compares actual 2021 excess deaths to simulations (counterfactuals) that are supposed to predict the trajectory of excess deaths in each country if no vaccines had been introduced (i.e. by running multiple simulations of the above fitted models after removing the effects of vaccines). The difference between these counterfactual curves and actual excess deaths result in the estimated deaths averted due to vaccination.

The authors’ models do not appear to account for evolution of the infectivity or lethality of the virus, other than explicitly modeling an increase in infection hospitalization rates due to the Delta variant (see 1.2.3 Variants of Concern section in the Supplement). The primary assumption in the counterfactual simulations is that excess deaths are explained by the “natural” evolution of the virus as reflected in its time-varying transmissibility, which can only be inferred (fitted) and not validated.

If the models assume parameters that over- or misestimate vaccine effectiveness against transmission, infection and death as well as the duration of vaccine protection, while ignoring other sources of pandemic-related excess deaths, this will lead to an over- or misestimation of time-varying virus transmissibility in order to achieve a good fit with the excess death curves in each country. This in turn, would artificially inflate the estimated excess deaths when the effects of vaccination are subsequently removed from the counterfactual simulations. We elaborate on these points below.

The Models in Watson et al. Rely On Unrealistic Assumptions About Vaccine-Derived Immunity

It is not clear whether the authors consider waning vaccine effectiveness in their models, and it appears that all their models assumed constant vaccine protection across the entire one-year study period, even though studies have suggested it is somewhere between three to six months. The model they cite, Hogan et al. 2021 by default assumes “long-term” (i.e. >one year) vaccine protection (see Table 1. in Hogan et al. 2021).

In addition, virtually every study of vaccine efficacy or effectiveness either excludes or lumps symptomatic cases within 21 days of first dose or within 14 days of second dose with the “unvaccinated” comparator groups. This is problematic in light of evidence that COVID infectivity may increase almost three-fold during the first week post-injection (see Figure 1 in our commentary of the study). This suggests that reported vaccine effectiveness estimates that are based on lower case rates observed >six weeks post-injection may (at least partially) be accounted for by infection-, not vaccine-, induced immunity due to short-term increases in COVID-19 infectivity immediately following vaccination.

While the models in Watson et al. include a latency period between vaccination and when protection kicks in, they do not account for a potential increase in vaccine-induced infectivity and transmissibility during this period. Not accounting for this effect in the models would overestimate naturally evolving and time-varying virus transmissibility and thus inflate excess deaths in the counterfactual simulations that exclude vaccination effects.

Finally, the authors explored the impact of immune evasion from infection-derived immunity by conducting a sensitivity analysis to estimate the deaths averted by vaccinations with different immune escape percentages ranging from zero percent to 80 percent (see Supplementary Figure 4 in the original article). In these models, the authors make clear that they assume a constant (non-waning) vaccine protection which is an unrealistic assumption (see above paragraph). However, the authors do not appear to do a similar sensitivity analysis of immune evasion from vaccine-derived immunity, which is important given the point raised in the above paragraph.

Models Ignore Excess Deaths Due to Factors Other Than COVID-19

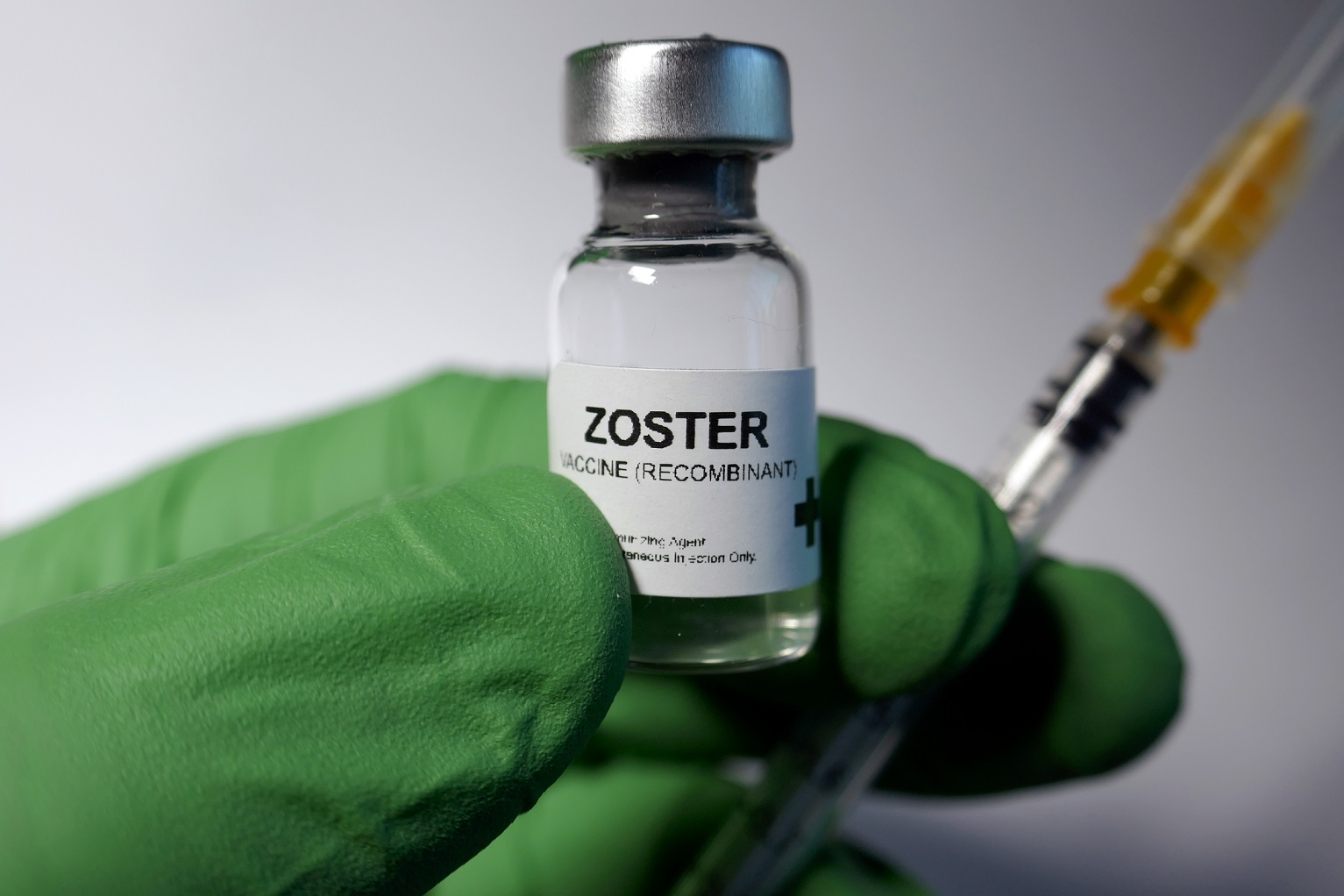

The fitted models and their counterfactuals assume that excess deaths in each country are explained solely by a naturally evolving COVID-19 virus and its (fitted model-inferred) time-varying transmissibility. The models do not attempt to account for excess deaths caused by other pandemic-related factors, for example the vaccines themselves as well as other nonpharmaceutical compulsory interventions. The CDC reports an overall vaccine-induced death risk of 0.0026 percent per dose based on the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, or VAERS. VAERS is a passive reporting system and may only capture—one percent of all vaccine-related side effects.

More recent independent lines of evidence using VAERS and credible assumptions about underreporting factors and ecological regression of publicly available vaccination and all-cause mortality data suggest VAERS may only capture—five percent of all vaccine-induced deaths. In addition, the models do not account for excess deaths resulting from other factors such as lockdown-induced “deaths of despair.”

By ignoring other potential sources of pandemic-related excess deaths in their models, the fitted models will over- and/or misestimate the effects of natural, time-varying virus transmissibility in order to achieve a good model fit with reported excess deaths, which in turn would lead to inflated excess death counts in their counterfactual simulations.

Lack of Face Validity

According to the authors’ country level estimates 1.9 million deaths were averted in the U.S. assuming a 61 percent vaccine coverage (see Supplementary Table 3 in original study). In the first year of the pandemic when no vaccines were available (2020), there were 351,039 U.S. COVID deaths. The authors’ models thus suggest that 1.9M / 350k = ~5.5x as many COVID deaths in the U.S. would have occurred in 2021 (vs. 2020) had no vaccines been introduced (see Figure 2 in our commentary of the study). This is highly implausible as there is very little reason to believe the virus would have naturally evolved to be that much more transmissible, infective and lethal.

The authors allude to higher transmissibility in 2021 due to the relaxing and/or lifting of public health measures and restrictions (lockdowns, travel restrictions, mask mandates etc.). However, the assumption that this could account for a >five-fold increase in COVID deaths in 2021 contradicts >400 studies that have concluded there were little to no public health benefits of these measures in reducing COVID outcomes.

Moreover, in 2021 (after vaccination was introduced), there were 474,890 U.S. COVID deaths. This is about 35 percent higher than 2021, suggesting crude evidence that mass vaccinations worsened COVID outcomes overall, consistent with observations of increased infectivity before vaccine protection kicks in (see 1st point above) and concerns of enhanced severity of COVID-19 disease caused by the vaccines based on preclinical studies.

Conclusion

While generative models are often a useful tool to simulate scenarios that have not occurred, inaccurate assumptions about model parameters can easily lead to model misspecification. In the case of Watson et al. 2022, they can lead to counterfactual simulations that grossly inflate estimates of deaths averted due to mass vaccinations.

Because such complicated modeling can be overly sensitive to input parameters, prone to overfitting and gives outputs that are difficult, if not impossible to validate, it should not be used to inform public health policy and guidelines. Quantitative risk-benefit ratio analyses that use clinical trial or real-world data to compare risks of specific outcomes, such as all-cause mortality or myopericarditis following vaccination and coronavirus infection, are much more informative and useful in this regard.

Note: I have posted a version of this article that includes figures and bibliography to ResearchGate, and tweeted the commentary to the original authors of the study in hopes for a response and rebuttal. I have also submitted a shortened version of the article as a 250-word letter to The Lancet Infectious Diseases and I am awaiting their reply. The author thanks Hervé Seligmann for helpful comments and feedback on the article.

This article was reprinted with permission. It was originally published by the Brownstone Institute. Dr. Spiro P. Pantazatos is Assistant Professor of Clinical Neurobiology (Psychiatry) at Columbia University. He is also Research Scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

If you would like to receive an e-mail notice of the most recent articles published in The Vaccine Reaction each week, click here.

5 Responses

There is no way they can say this with any assurance of truth. It’s merely speculation, as always with their ridiculous calls. Total BS.

Simple: When the “pandemic” was in full swing, I went past an ER and there was NOBODY there.

Post lethal injection and everyone got the jab, ER’s (and hospitals) are FULL.

Doesn’t anyone see the similarities of the cadeuceus and the thing in Baphomet’s lap?

Aug 2021 I also noticed a increase of IL hospital ER visit.

The biggest increase was In April 2021 when the most ??.

The ER visit didn’t go down by August.

No conclusion on what caused increase of ER. Wasn’t COVID. Could ? cause ER after 4 months? Or did lifting the lockdown increase ER visit?

I do not trust any of their ‘statistics’. The more “official” the source the more prone to lies they are.

We know that the model is wrong.

But what is right?

Where is your better or best model?

We must compare vaccinated verses unvaccinated, of same health age and environment.

How many live would we have saved if we didn’t fund biological wepon?

How many lives would we have saved with vitamin D3, vitamin C, & zinc?

How many lives would we have saved with ivermectin. & Hydrocodone?…