- Excess dietary sugar has been linked to increased risk of developing not only obesity, tooth decay, and fatty liver disease but also heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- The mechanism behind many of these sugar-induced disorders is insulin resistance, in which the body stops responding normally to insulin and disrupting the processing of glucose into usable energy.

- Since there is no known cure for Alzheimer’s disease, dietary and lifestyle changes are critical to reduce the risk of developing this destructive brain disorder.

It is hard to comprehend the degree of damage perpetrated by sugar, one of the most wildly popular and ubiquitous ingredients in the typical Western diet. Consumption of sugar has already been identified as a leading risk factor in obesity, tooth decay, fatty liver disease, insulin resistance leading to diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, cancer, and heart disease.1 It has been likened to any other addictive substance in its effects on the brain and its manipulation of dopamine and serotonin levels.2 Sugar has also been linked to an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.3

Researchers report that a higher percentage of added sugar in the diet increases the risk of dying from heart disease, even when taking into consideration such confounding factors as age, body mass index, gender, degree of physical activity, or an otherwise healthy diet.4 The provocative factor appears to be sugar’s effect on insulin resistance: Sugar generates a spike in insulin levels, which over time damages the epithelial lining of blood vessels and leads to stiffening of the vessel walls that creates a hospitable environment for many known cardiac risk factors.5 A similar mechanism seems to drive the increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Insulin Resistance May Be the Key

Insulin, and its partner, glucagon, are the hormones critical to the regulation of blood glucose (or blood sugar), which the body uses for energy. Described as “the yin and yang of blood glucose maintenance,” the hormones balance blood sugar and work in tandem to keep levels within the narrow range needed for normal activity. Immediately after a meal, the pancreas releases insulin to help cells use the blood sugar generated from the digested food. Unused blood sugar is stored in liver and muscle tissues as glycogen or as fat. Between meals, glucagon is released to convert stored glycogen to usable glucose, helping to keep blood sugar levels steady.6

The term “insulin resistance” is used to describe a condition in which the body’s metabolic tissues stop responding normally to insulin, which results in a decreased ability to absorb blood glucose, and creates the perceived need for more insulin.7 It is one of the “earliest detectable changes in the progression to diabetes.”8 In fact, the association between sugar and dementia is so strong that Alzheimer’s has been called “type 3 diabetes,” a reference to the fact that Alzheimer’s disease shares many molecular and biochemical characteristics of diabetes but differs from types 1 and 2 diabetes in that the damage selectively involves the brain.9

According to a study out of Duke University, insulin resistance may develop in more than one way. These researchers suggest that one process is “triggered by excess sugar in the liver that activates a molecular factor known as carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein, or ChREBP.”10 They studied the effects of sucrose (the main dietary sugar in the human diet) on laboratory animals and corroborated their results in human liver samples and reported that, “Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that hepatic ChREBP serves as a sensor for dietary sugar ingestion.”11

The lead researcher, Mark Herman, MD, is quoted as saying:

We found that no matter how much insulin the pancreas made, it couldn’t override the processes started by this protein, ChREBP, to stimulate glucose production. This would ultimately cause blood sugar and insulin levels to increase, which over time can lead to insulin resistance elsewhere in the body.12

Alzheimer’s and Heart Disease Often Go Hand in Hand

Many risk factors for heart disease are also associated with Alzheimer’s and include smoking, alcohol use, diabetes, high fasting blood sugar levels, and obesity.13 In an interview with Joseph Mercola, DO, David Perlmutter, MD says, “anything that promotes insulin resistance will ultimately also raise your risk of Alzheimer’s.” Going further than the general observation that even mildly elevated blood sugar levels of 105 or 110 are associated with an increased risk of dementia, Dr. Perlmutter recommends that blood sugar levels should not exceed 95 at most, and that the “ideal fasting blood sugar level is somewhere around 70 to 85.”14

Accepting that an insulin-resistant brain is at risk for development of Alzheimer’s, it follows that anything that protects the insulin balance is crucial for avoiding not only this devastating condition but also many other scourges of modern life, including heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Insulin-Protective Dietary and Lifestyle Habits

The typical American diet, high in processed foods and added as well as hidden sugars (see “Sugar Nation: Is Sugar the New Alcohol?”), is a major culprit in the increasing risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Since there is no known cure for Alzheimer’s disease at this point, that is actually good news, since diet is a modifiable risk factor.

For optimal functioning, the brain needs a good supply of healthy fats from, for example, avocados, coconut and raw nut oils, raw butter and dairy, pasture-raised or grass-fed meats and poultry, and organic egg yolks.15 Fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, vitamins, and minerals are equally important. Some foods specifically said to be “brain boosters” include leafy green vegetables (which provide magnesium and folate, both critical to brain health), salmon and other cold-water fish (though high mercury levels of many fish may contribute a whole different set of health issues), berries and dark-skinned fruits, coffee and chocolate, extra virgin olive oil, and cold-pressed virgin coconut oil.16

Dr. Mercola offers some other simple guidelines for improving the diet to reduce the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Key is avoiding sugar and fructose, but Dr. Mercola also recommends avoiding gluten in general, eating fermented foods to optimize the gut flora, and reducing overall calorie consumption or intermittently fasting.17

Conversely, brain health is hampered by an overabundance of complex carbohydrates, processed foods, and sugar. These foods produce toxins, which can lead to inflammation and a build-up of plaques in the brain, and cause damage to cognitive function. Particularly harmful foods include processed meats and cheeses; “white foods” such as pastas, breads, rice, and added sugar; microwaveable popcorn; and beer.18

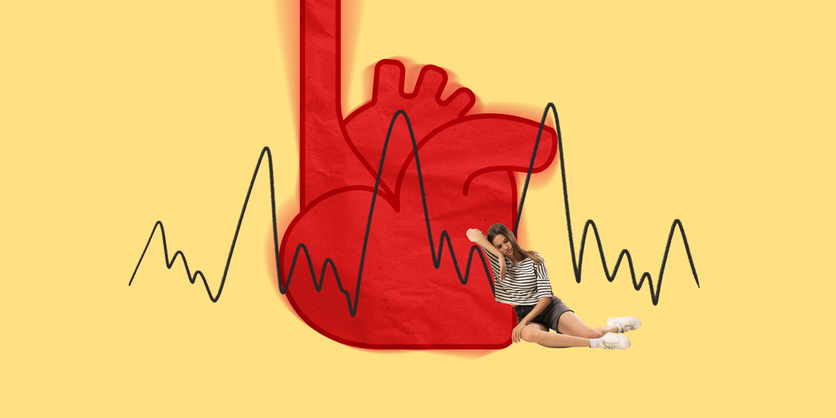

In addition to dietary considerations, lifestyle habits that can help protect against Alzheimer’s disease, among other disorders, include daily exercise—both physical and mental, optimizing vitamin D levels, avoiding or minimizing exposure to both aluminum and mercury (the flu shot, for example, may include a mercury preservative, Thimerosal, and other vaccines may contain aluminum adjuvants), and avoiding anticholinergic and statin drugs.19

References:

1 Gunnars K. 10 Disturbing Reasons Why Sugar is Bad For You. Authority Nutrition 2016.

2 Trading Alcoholism for Sugar Addiction: Here’s the Not-So-Sweet Truth. Promises Treatment Centers Sept. 24, 2013.

3 High Blood Sugar May Contribute Towards Alzheimer’s Disease, New Study Finds. Alzheimer‘s Society May 5, 2015.

4 Corliss J. Eating Too Much Added Sugar Increases the Risk of Dying With Heart Disease. Harvard Health Publications Dec. 1, 2015.

5 Sinatra S. Sugar is a Major Cause of Heart Disease. DrSinatra.com Oct. 11, 2016.

6 Morris SY. How Insulin and Glucagon Work. Healthline Aug. 26, 2014.

7 Prediabetes and Insulin Resistance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases August 2009.

8 Duke Health. New Theory on How Insulin Resistance, Metabolic Disease Begin. Science Daily Sept. 26, 2016.

9 de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Alzheimer’s Disease Is Type 3 Diabetes–Evidence Reviewed. J Diabetes Sci Technol November 2008.

10 See Footnote 8.

11 Kim MS et al. ChREBP Regulates Fructose-Induced Glucose Production Independently Of Insulin Signaling. The Journal of Clinical Investigation Sept. 26, 2016.

12 See Footnote 8.

13 Mercola J. Alzheimer’s: A Disease Fed by Sugar. Mercola.com Aug. 13, 2015.

14 Ibid.

15 Mercola J. Alzheimer’s Disease—Yes, It’s Preventable! Mercola.com May 22, 2014.

16 Wegerer J. Nutrition and Dementia: Foods That May Induce Memory Loss & Increase Alzheimer’s. Alzheimers.net Jan. 2, 2014.

17 See Footnote 15.

18 See Footnote 16.

19 See Footnote 15.