- Species-specific mothers’ milk is perfectly suited to the needs of young mammals and provides benefits far exceeding simple nutrition alone.

- In humans, the prevalence of an antibody known as Immunoglobulin A (IgA) in breast milk protects the infant from potentially harmful pathogens common to the environment of mother and baby.

- Breast-fed infants are able to neutralize live rotavirus vaccines, yet mount a more vigorous inflammatory response to other vaccines, reflecting a more mature immune system compared to formula-fed infants.

With nearly 80 percent of mothers in the United States now choosing breastfeeding over formula feeding for their babies,1 there clearly is widespread agreement that mothers’ milk is the ideal food for the very young. This source of nutrition is also perfectly species-specific: Cow’s milk is best for rapidly growing bovine calves, whale milk is uniquely suited to the high-fat needs of the whale calf, and human milk has exactly the right combination of nutrients and antibodies needed to fully support the healthy growth and developing immune system of a human infant.2

Breastfeeding is said to provide increased emotional security for the baby, as well as lower cost, ready access compared to formula preparation, and major health benefits for both the baby and the breastfeeding mother. There are many reasons breastfeeding might not be an option, and formula-fed infants can certainly grow up well bonded and healthy, but breast milk does appear to offer important advantages that merit attention.

Maternal Benefits of Breastfeeding

For the mother, lactation triggers contractions that quickly control postnatal bleeding, the calories burned in making milk can help new mothers more quickly shed gestational weight, and nursing creates forced quiet time to de-stress and focus on the bond between mother and child.

Women who breastfeed also have a decreased risk of developing premenopausal breast cancer, ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome (a cluster of disorders that may occur together to incrementally increase the risk for heart disease, stroke, or diabetes. Co-existing conditions may include high blood pressure, increased blood sugar, excess fat around the midsection, and atypical cholesterol levels3).

For the baby, breast milk goes beyond basic nutrition to provide irreplaceable immunologic and physiologic benefits that may help them avoid such later health problems as digestive issues, ear infections, anemia, obesity, and diabetes, all more common in formula-fed babies.4 Breastfed children are also known to have fewer problems with jaw alignment and fewer speech problems later in life.5

Impact of Breast Milk on Infant Immunity

One of the most important functions of breast milk in the very young is its support of the developing immune system. In the first few days of life, breast milk is really colostrum—an antibody-rich brew that helps protect the newborn from environmental challenges and jumpstarts the infant’s microbiome by seeding the intestine with microbes from the mother.6

Human milk also establishes a gut environment that promotes colonization with beneficial flora and protects against such infections as H influenzae, S pneumoniae, V cholerae, E coli, and rotavirus. The benefits to the baby’s immune defenses may help explain the higher incidence of allergic disease reported among formula-fed children.4

Breast Milk/Immune Function Synergy

There is much evidence to indicate that breastfeeding is an important player in several phases of the developing immune system. Though the many confounding factors make it difficult to ascertain the precise role of breast milk in each step, “Fundamental changes in the infant’s immune system as a result of premature cessation of breastfeeding could lay the groundwork for later dysfunction in the immunologic controls necessary to prevent autoimmune disease or hypersensitivity reactions.”7

One way in which breast milk influences the developing immune system is through antibody sharing. The human body produces several types of antibodies, or immunoglobulins, identified as IgG, IgA, IgM, IgD, and IgE. All are found in breast milk, but the most common is IgA, specifically the form known as secretory IgA, which is also abundant on cells throughout the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of adults. IgA acts by protecting the molecules from gastric acid and digestive enzymes.

These antibodies are not digested by the baby, but form a protective coating over all the internal surfaces, shutting out microbes that could cause harm.8 The passive supply of antibodies provided by the mother’s milk temporarily protects the infant against pathogens the mother has been exposed to, which naturally reflect the most common microbes found in the environment of both mother and baby.9 In contrast, formula-fed babies are not protected against ingested pathogens for weeks or months, until they begin making their own secretory IgA.10

Unlike other antibodies, the abundant secretory IgA molecules in breast milk ward off disease without causing inflammation, which is a normal defensive response to pathogens but may be damaging to the infant’s developing gut.10 Vaccines act by triggering this very inflammatory response, potentially overriding the breast-fed baby’s systematic development of a healthy immune response.

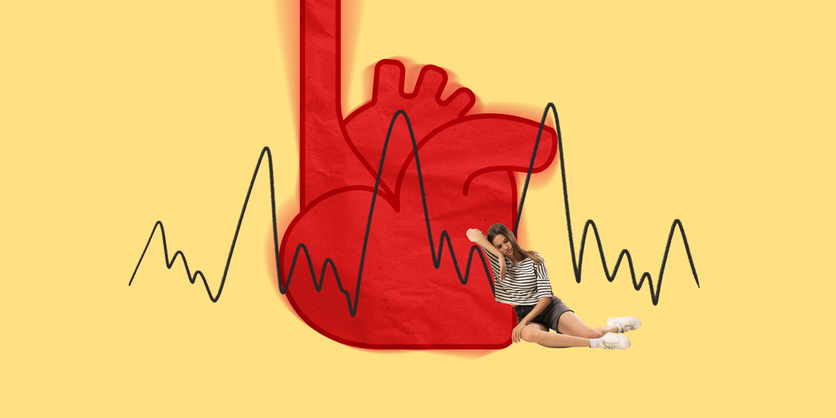

Impact of Vaccination on the Breast-Fed Immune System

Vaccines can interact with breastfeeding by two different mechanisms. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study that initially raised concern among breastfeeding advocates, for example, showed that the antibodies in breast milk are able to effectively neutralize the live oral rotavirus vaccine.11

The CDC suggestion that delaying breastfeeding for a few hours around the time of vaccination might circumvent the issue and give the vaccine a chance to work sparked outrage, as it seemed to suggest that vaccinating was more important than breastfeeding, ironic given that rotavirus is one of the infectious diseases that breast milk protects against. The CDC countered that it was not recommending vaccination in lieu of breastfeeding but was suggesting that the link be studied in countries where rotavirus is particularly dangerous.12

Aside from the possibility that breast milk could neutralize some live-virus vaccines, studies have also shown that breastfed babies have more well-developed immune systems than formula-fed babies and tend to mount a more vigorous response to other vaccines, as reflected by an increase in the presence of vaccine-induced antibodies compared to formula-fed infants. Since increased antibody level proves only an active inflammatory response to the injected substances, breast-fed babies are actually responding to vaccination with a more vigorous physiologic protest against the injected antigens and adjuvants.

All things considered, breast milk is truly a fascinating fluid that supplies infants with far more than nutrition. It protects them against infection until they can protect themselves.10

References:

1 Smith A. Why Breastfeed? Breastfeeding Basics c. 2016.

2 Rust R. Amazing Mammal Mothers Making Milk. Breastfeeding USA 2015.

3 Mayo Clinic Staff. The Metabolic Syndrome. Mayo Clinic Mar. 19, 2016.

4 Stuebe A. The Risks of Not Breastfeeding for Mothers and Infants. Obstetrics and Gynecology Fall 2009.

5 Breastfeeding: The Perfect Food for Babies. Nutrition MD.

6 Mihalovic D. Why Breastmilk Does What a Vaccine Never Could. Prevent Disease Signs of the Times.net Sept. 14, 2016.

7 Jackson K, Nazar A. Breastfeeding, the Immune Response, and Long-term Health. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association April 2006.

8 Breastfeeding and Immunity. Australian Breastfeeding Association June 2013.

9 The Immune System and Vaccination. Immunisation Advisory Centre, University of Aukland Feb. 24, 2012.

10 Newman J. How Breast Milk Protects Newborns. KellyMom.com Aug. 1, 2011.

11 Moon SS, etal. Inhibitory Effect of Breast Milk on Infectivity of Live Oral Rotavirus Vaccines. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Journal (PubMed.gov) October 2010.

12 ABM President responds to Vaccines and Breastfeeding. Breast Feeding Medicine Jan. 28, 2012.